Introduction

This brief will examine the quantitative and spatial evidence about the following aspects of institutional support for the delivery of water services:

- Water service authorities (WSAs) and water boards.

- The financial standing of water service authorities

- The capacity of water service authorities for the delivery of adequate water services.

Water service authorities and water boards

Water service authorities are either local municipalities[1] or district municipalities within which local municipalities are located. They are responsible for the distribution of water within their jurisdictions. Five provinces (Free State, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape and Western Cape) have only local municipal WSAs, whereas the other four have a mixture of local and district municipal WSAs. In 89 local municipalities, the WSA is a district municipality (21 district municipalities are WSAs) and in the remaining 124 local municipalities are themselves the WSAs. There are 145 WSAs in all[2].

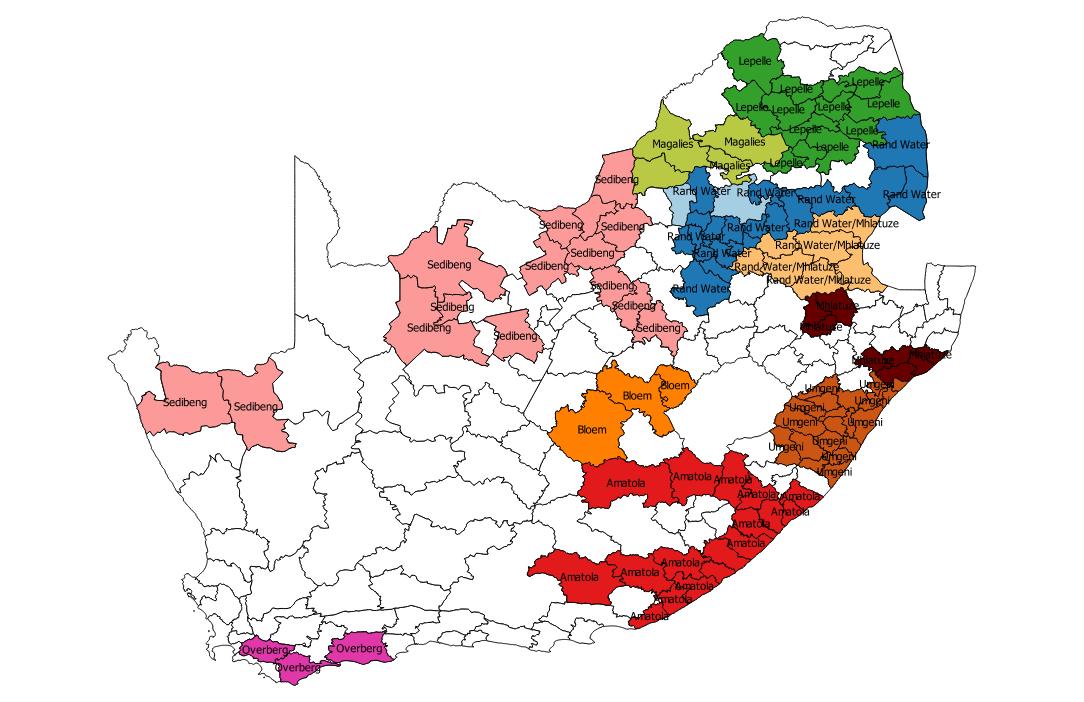

The supply of bulk water to water service authorities may be provided by water boards, which themselves obtain water from nationally regulated water sources. The areas of supply of water boards do not cover the whole country. Some water service authorities obtain water from local sources under a system of water abstraction rights registered with the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS). 110 local municipalities are supplied through water boards, and 103 are not. The map shows the extent of water board supply[3].

Accordingly, local municipalities can be classified in two ways:

- whether the WSA serving them is the local municipality itself or a district municipality

- whether the municipality is within the area of supply of a Water Board

The legal frameworks for water services authorities and water boards are outlined in earlier briefs in this series.

The financial standing of WSAs

The Auditor-general’s report for 2016/17 categorises Municipal Finance and Management Act audit outcomes audit outcomes into six categories. Table 1 indicates the distribution of WSAs across them:

Table 1

|

Audit outcomes |

Local municipality WSAs |

District municipality WSAs |

|

Financially unqualified with no findings |

21 |

1 |

|

Financially unqualified with findings |

44 |

7 |

|

Financially qualified with findings |

33 |

8 |

|

Adverse with findings |

2 |

|

|

Disclaimed with findings |

12 |

3 |

|

Audit not finalised at legislated date |

14 |

|

|

TOTAL |

124 |

21 |

Note: Findings relate to non-financial aspects of local government management. Their presence indicates material defects in these aspects. Financially unqualified means that the Auditor-General has found no grounds for a negative evaluation of the accounts submitted for audit.

The National Treasury’s The State of Local Government Finances and Financial Management as at 30 June 2017 report calculated a financial stress indicator. Municipalities with scores of 16 or above are regarded as financially distressed. The distribution of stress scores across local and district municipalities is set out in Table 2.

Table 2

|

Financial stress scores |

Local municipality WSAs |

District municipality WSAs |

|

8-10 |

5 |

1 |

|

11-13 |

23 |

3 |

|

14-15 |

27 |

6 |

|

16-17 |

22 |

4 |

|

18-19 |

29 |

6 |

|

20+ |

18 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

124 |

21 |

69 local municipality WSAs and 11 district municipalities were financially distressed, representing just over half all WSAs.

Water supply capacity

The DWS National Water Service Knowledge System supplies information on four key variables bearing on the capacity of WSAs, as self-assessed, in 2017/18. These are:

- Water services planning

- Technical staff capacity

- Water conservation and water demand management

- Infrastructure asset management

Each variable is represented by a score between zero and 100. The average score across these variables is taken as an indicator of water supply capacity.

Relationship between the variables

The question then arises: what are the effects of (a) conditions leading to poor audit outcomes and (b) financial stress on water supply capacity?

We have three ordinal variables:

- Auditor-General audit outcomes (excluding the unfinalised category): the higher the score, the worse the situation.

- Financial stress scores: the higher the score, the worse the situation.

- The capacity score: the higher the score, the better the situation.

Correlations[4] between the variables are as follows:

- Audit outcomes and financial stress scores: 0.29

- Audit outcomes and capacity scores: -0.36

- Financial stress and capacity scores: -0.29

These correlations are all significantly different from zero[5] at the 5% level, and the correlations have the expected sign, but the coefficients are low. This means that there are WSAs with poor audit outcomes and high levels of financial distress which assess their water supply capacity as relatively good and there are WSAs with good audit outcomes and low levels of financial distress which assess their water supply capacity as relatively poor.

The point can be illustrated in yet another way. Table 3 sets out average capacity scores by audit outcome and financial distress.

Table 3

|

Financially OK |

Financially stressed |

TOTAL |

|

|

Financially unqualified |

67.0 |

60.5 |

63.8 |

|

Other audit outcome |

63.2 |

52.9 |

57.4 |

|

TOTAL |

65.1 |

56.2 |

60.3 |

Conclusion

The results suggest the following interpretation. A poor audit outcome indicates disorganization, incompetence and/or corruption within a WSA. Financial stress indicates lack of resources within a WSA. The association suggests that these factors are related, but not strongly: lack of resources, occasioned by weak local fiscal conditions do not necessarily entail disorganization, incompetence and corruption, nor is disorganization, incompetence and corruption confined to WSAs with a poor fiscal base. Moreover, while poor audit outcomes and financial stress have an adverse effect on self-assessed water supply capacity, the relationship is limited. A major limitation of this finding, however, is that self-assessed water supply capacity is not necessarily perfectly correlated with actual water supply performance.

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

charles@hsf.org.za

[1] Metros are here regarded as local municipalities

[2] The list of WSAs is taken from the DWS’s National Water Services Knowledge System. .

[3] Information provided by the Department of Water and Sanitation

[4]These are polychoric correlations, appropriate for ordinal variables

[5] A coefficient of zero indicates no association between the variables, while a coefficient of 1 or -1 indicates perfect correlation. Regression analysis with the capacity score as dependent variable yields the following coefficients:

|

Impact on capacity score |

|

|

Audit outcomes |

|

|

Financially unqualified, no findings |

Omitted category |

|

Financially unqualified, findings |

-8.6 |

|

Financially qualified, findings |

-7.8 |

|

Adverse |

-18.9 |

|

Disclaimed |

-18.1 |

|

Accounts not submitted |

-13.0 |

|

Financial stress |

-0.9 |

|

R2 |

0.15 |

All coefficients are significantly different from zero at the 5% level, and they all have the expected sign. The low R2 confirms the finding that the associations are weak