Introduction

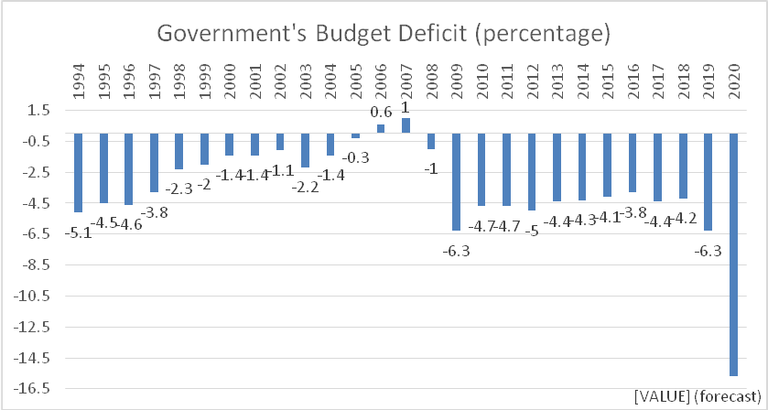

Following the declaration of national disaster in March 2020 and the prolonged lockdowns which followed, the South African fiscus, already in poor shape, is under even more pressure. This comes after over a decade of financial mismanagement by government and a move to below investment grade by the ratings agencies. In the 2020 Supplementary Budget, the budget deficit was forecast at 15.7 percent of GDP in 2020/21 fiscal year, compared to 6.4 percent in 2019. Even if the tax revenue shortfall is not as high as projected[1], it will still be by far the largest budget shortfall since the end of apartheid.

Without credible solutions to the shortfall, government risks running out of funds to repay all its outstanding debt and provide sufficient essential services to its population. Treasury’s intention is to freeze public sector wages for the next three years, its largest budget item, is now being contested before the Constitutional Court. But, even if it is successful in the Con Court, it will still need to raise funds elsewhere. Among the possible sources of funding are the route the apartheid government took of prescribed assets, bilateral loans from other countries, or an additional loan facility from the IMF. However, it is doubtful that any or all of these will be of the scale required, and the main source of funding is still likely to be weekly bond auctions.[2]

Following the spike in yields from auctions of government bonds in March 2020, which triggered Reserve Bank intervention to stabilise the markets, commentators have wondered whether disorderly conditions would return. For now, however, the government has no difficulty in selling its bonds and the government bond yield curve is currently lower than it was six months ago, except at the very short end[3]. R 6.6 billion of fixed interest bonds and R 2.0 billion of inflation-linked bonds are currently being sold each week.

Why short-term bonds?

Short-term bonds are preferred to long-term for two related reasons. First, short-term bonds have markedly lower interest rates than government’s long-term bonds, i.e. the yield curve remains steep. Second, as per October 2020’s medium term budget speech, interest payments on outstanding debt at 4.8% of GDP are the fastest growing spending item, consuming 21% of the main budget revenue and 11.1% of government spending, making it the fourth biggest spending item behind social development, basic education, and health. Therefore, interest rates on any increases in government debt need to be kept to a minimum. The disadvantage of short-term bonds is that they have to be rolled over soon. A high reliance on them makes financing more vulnerable to sudden stops and a marked shift towards them often indicates a rising level of fiscal distress.

Increased funding from a full allocation of weekly short-term Treasury bonds auctions

To find out how much more funding could have been raised by a full allocation to bidders, and at what interest rates, this brief, as well as the previous brief, uses information from the Treasury’s bond auctions during the two months preceding the lockdown up until the end of December 2020.[4]

The results of our study are as follows:

|

Fixed rate bonds |

Inflation-linked bonds |

|

|

Total bids not allocated (ZAR) |

424,240,000,000 |

83,340,000,000 |

|

Average premium (%) |

0.105 |

0.044 |

To calculate how much more funding could have been raised by a full allocation to bidders for bonds, we subtracted the amount of bonds that were allocated at each auction from the amounts that were bid for by buyers. This gave a total of R 507,58 billion that could have been raised (R 424,24 bn + R 83,34 bn) in these auctions from the beginning of April to the end of December.[5] This calculation is likely to be an overestimate, since greater allocation in one week may lead to fewer bids in the next.

The additional R 507,58 billion, however, would have been sold at higher yields, as shown by the ‘Average premium %’ above (the average of each auction’s new yield % minus its weighted average yield %).[6] The bid/allocation ratios also change according to circumstances. Therefore, if South Africa’s situation becomes less manageable in the eyes of investors, the premium will become greater and the bid/allocation ratios smaller, meaning less potential funding at a higher cost.

Short term bonds, maturing in 2023 or sooner, accounted for 8.0% of fixed-interest bonds and 14.6% of inflation-linked bonds at the end of January 2021. There are limits to the reliance which can be placed on increased sales in this sector.

Conclusion

With the South African government needing to raise more funds to try and alleviate the effects the COVD-19 pandemic on its budget shortfall, one of the possible sources of funds is the domestic capital market, through an increased allocation of lower yielding short-term government bonds.

However, as shown by the steeply upward sloping yield curve, which makes longer-term bonds more expensive, unless investor confidence is restored via much needed structural reforms to the economy, which all economists concerned about the South African economy agree upon[7], movement towards reattaining an investment grade rating by the agencies will not happen, and government’s funding options will remain limited and expensive .

Charles Collocott

Policy Researcher

charles.c@hsf.org.za

[1]https://www.businesslive.co.za/bt/business-and-economy/2021-01-24-better-tax-take-raises-budget-hopes/

Also see, BusinessTech, South Africa tax collection could be R 100 billion more than expected, 5 February 2021

[2]https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/columnists/2020-04-20-carol-paton-thinking-on-role-of-the-state-and-reserve-bank-needs-to-be-upended/

[3]See World Government Bonds at http://www.worldgovernmentbonds.com/country/south-africa/ accessed on 8 February 2021.

[4] The bonds included are: R2013, R2030, R2032, R2035, R2037, R2040, R2044, R186, I212, I2025, I2029, I2033, I2038, I2046, and I2050,

[5] This in addition to R 71,88 billion that could have been raised over February and March, as noted in the previous brief.

[6]The new yield % = reported average yield * worst bid/clearing yield.