Introduction

Two years ago, Malusi Gigaba tabled a Medium Term Budget Policy Statement which pointed out that South Africa had a major fiscal problem requiring tough decisions, but failed to take any of them. He was roundly criticized as a result. Now we have a new Minister of Finance, but the same approach. He has presented projections which fail to meet his stated target of reducing the primary budget balance, excluding financial support for Eskom, to zero by 2022/23, merely stating achieving the fiscal target will require large additional adjustments exceeding R 150 billion over three years. On this, he is right as Table 1 shows:

Table 1

|

Main budget |

|||||

|

Primary balance excluding financial support for Eskom |

|||||

|

Rand billion |

|||||

|

2019/20 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

Total |

|

|

MTBPS as presented |

-71.5 |

-86.5 |

-83.6 |

-67.7 |

|

|

Target |

-46.7 |

-23.8 |

0 |

||

|

Gap |

-39.8 |

-59.8 |

-67.7 |

-167.3 |

|

Notes:

- The main budget is financed from the National Revenue Fund

- The reduction in the primary balance is assumed to reduce linearly between 2019/20 and 2022/23

If these adjustments can be foreseen as necessary to implement the Minister’s goal, why have they not been incorporated throughout the document? That is what informed members of the public were looking for, and all they have at present is a promise that the final adjustments will be announced in the 2020 Budget.

The purpose of this brief is to sketch an answer to the question that the Minister has not answered.

Assumptions

- The Minister believes that there is only moderate scope to boost tax revenue, but states that additional tax measures are under consideration. Let’s assume that a third of the gap is to be financed by them, and that just two tax rates are changed - personal income tax and value added tax. The proceeds of the increases in tax from the two sources are assumed to be the same.

- This leaves two-thirds of the gap to be financed by reductions in expenditure. The Minister is taking aim at the public sector wage bill, so let’s assume that two-thirds of the two-thirds of the gap will be financed by its reduction, and the remainder of the gap will be financed by non-wage public sector expenditure. Social grants are assumed to remain constant when deflated by the consumer price index, with needs growing at the same rate as targeted age groups. Remaining non-wage expenditure is assumed to be cut at a constant rate across the board.

Results

The package which results from these assumptions has the following features:

- An increase in the average personal income tax reaching 1.8% of PIT paid in 2022/23

- An increase in the VAT rate to 15.4% in 2022/23

- A decrease in the public sector wage rate of 1.7% compared with the MTBPS baseline in 2022/23.

- A decrease in public sector employment of 1.7% compared with the MTBPS baseline in 2022/23.

- An average increase of 5.1% per annum in current prices for the public sector wage bill.

- An average increase of 6.4% per annum in current prices for social grants.

- An average increase of 3.1% per annum in current prices for other non-wage public expenditure.

- A reduction of 1.4% in household gross disposable income compared with the MTBPS baseline in 2022/23.

- A virtual stagnation in expenditure per capita on publicly provided health services to 2022/23.

The Appendix sets out the supporting calculations.

Of course, if the assumptions were fed into a general equilibrium model, the results would be somewhat, but probably not greatly, different.

The package spreads the burden of adjustment throughout the economy. The mix can be adjusted at will.

From a political point of view, resistance to an adjustment package of this sort would be led by the public sector trade unions. The drop in employment is well below the attrition rate in the public service, so the adjustment in employment can be managed without major retrenchments. But downward pressure on the wage rate will be strongly resisted by a sector which has enjoyed rising real wages for many years. The unions are gearing up for a fight[1], and confrontation between them and the government is coming. Depending on the outcome, the wage and employment mix in the adjustment will vary, and the unions may succeed in blowing a large hole through the government’s objective of reducing the primary deficit to zero in the next three years.

Is the MTBPS a framework for ‘austerity’? If not, would austerity be introduced by the adjustment? If so, would an adjustment be unnecessarily austere?

The MTBPS as it stands (i.e. without the adjustment) is not austere. Growth picks up from 0.5% in 2019 to 1.7% in 2022. Given that the MTBPS puts expected long-term growth rate (effectively, the potential growth rate) at between 1.0% and 1.5%, the economy will be overheating slightly at the end of the period, even though real per capita GDP will be rising at no more than 0.5%. It will be the low level of potential growth, rather than aggregate demand, which will be the constraint then.

Whether the MTBPS with adjustment would be austere would depend on what happens to monetary policy. Aiming for the mid-point of the inflation targeting band permits, indeed requires, more expansionary monetary policy, implying lower short term interest rates. So fiscal tightening coupled with continuing inflation targeting implies that the MTBPS with adjustment would not be austere in macroeconomic terms. On this view, and provided that economic risk arising from the political sphere does not increase (and preferably diminishes), one might see greater private sector investment, output and employment offsetting public sector contraction, in a way not included in the calculations set out above.

But ‘austerity’ can have another meaning, and it probably does in the popular imagination, as it refers to downward pressure on household disposable income and the ‘social wage’ i.e. public services provided free of charge or at a subsidized rate. From this point of view, the adjustment package is austere, but it is necessarily so. Partly as a result of incompetence and corruption in state owned enterprises and partly because the state has used up its fiscal space too fast since the onset of the global financial crisis, the government has got itself into an unsustainable fiscal position. It has the prospect of getting out of the hole it has dug for itself with a package which, although painful, will not produce the massive, wrenching dislocation that awaits down the line if the adjustment is not effected soon.

Public debt

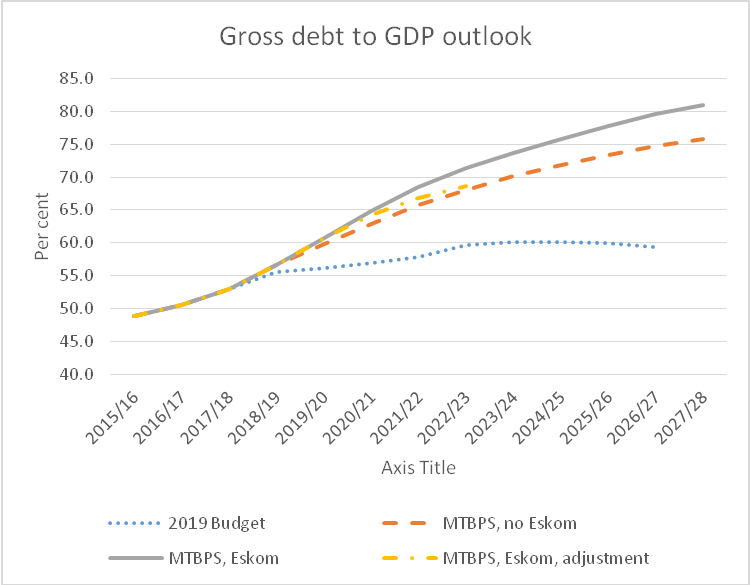

The most alarming item of information in the MTBPS is the projection of the gross public debt to GDP ratio up to 2027/28. The graph below reproduces the figure in the text, augmented by a projection of the position as it would be if the adjustment were applied up to 2022/23. The deterioration since the Budget is massive and the MTBPS projects a continuously increasing ratio all the way out, compared with the Budget projection of a peak in 2023/24. In the worst case, the MTBPS as it stands with Eskom financing taken into account, the ratio exceeds 80% at the end of the period, a full 20% higher than the Budget projection peak. Even taking the adjustment into account, the trajectory is a rapid rise.

Moreover, each of the trajectories graphed below represent expected values, around which hover a cloud of risk. The MTBPS contains a fiscal risk statement which discusses macroeconomic risks, expenditure risks, contingent and accrued liability risks and long term economic and fiscal risks. A perfect storm would take the form of economic growth coming in lower than expected, the next public sector wage increase coming in higher than expected, continuing management failures in state owned enterprises leading to continuing demands for bail outs to avoid loan defaults and pressures from the health and higher education systems for increased expenditures in relation to GDP.

Conclusion

South Africa has a reputation for sound macroeconomic management and it has never defaulted on its loans. But the risks to the fiscal position are severe, partly as a result of incompetence and corruption and partly because of bad luck in the form of an uncertain global economic environment. The political risk of a populist adventure has never been higher since 1994. Neither have the costs of such an adventure been greater. Fractious politics may increase conflict between South African elites so severely that the fiscal system falls apart, and then where shall we be?

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

charles@hsf.org.za

Appendix

Table A1

|

Main calculation |

|||||

|

Rand billion |

|||||

|

2019/20 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

Average annual increase |

|

|

Projected GDP |

5131.7 |

5448.9 |

5804.4 |

6187.4 |

|

|

Revenue |

|||||

|

Required increase |

13.3 |

19.9 |

22.6 |

||

|

PIT |

527.6 |

560.2 |

596.8 |

636.1 |

|

|

Increase as a percentage |

1.2% |

1.7% |

1.8% |

||

|

VAT |

325.9 |

346.0 |

368.6 |

392.9 |

|

|

VAT rate |

15.0% |

15.3% |

15.4% |

15.4% |

|

|

Expenditure |

|||||

|

Main budget non-interest expenditure |

1479.6 |

1568.5 |

1644.9 |

1718.6 |

|

|

Public sector |

|||||

|

Wage bill: national |

630.7 |

675.2 |

717.6 |

758.5 |

|

|

Wage bill: provinces and municipalities |

83.1 |

88.0 |

94.7 |

100.8 |

|

|

Wage bill: higher education |

18.6 |

19.0 |

19.8 |

20.3 |

|

|

Total wage bill |

732.4 |

782.2 |

832.1 |

879.6 |

|

|

Per cent reduction |

2.3% |

3.2% |

3.4% |

||

|

Revised wage billl |

732.4 |

764.5 |

805.5 |

849.5 |

5.1% |

|

Wage level |

100.0 |

98.9 |

98.4 |

98.3 |

|

|

Employment level |

100.0 |

98.9 |

98.4 |

98.3 |

|

|

Non-wage public expenditure |

747.2 |

786.3 |

812.8 |

839.0 |

|

|

Less social grants |

175.3 |

185.9 |

198.4 |

211.4 |

6.4% |

|

Reducible public expenditure |

571.9 |

600.4 |

614.4 |

627.6 |

3.1% |

|

Per cent reduction |

1.5% |

2.2% |

2.4% |

||

|

Impact on household gross disposable income |

|||||

|

Baseline |

3109.8 |

3302.0 |

3517.5 |

3749.6 |

|

|

Increase in taxation |

13.3 |

19.9 |

22.6 |

||

|

Drop in public sector wage bill |

14.2 |

21.3 |

24.1 |

||

|

Reduction in procurement |

3.5 |

5.3 |

6.0 |

||

|

Total drop in HGDI |

31.0 |

46.5 |

52.7 |

||

|

Per cent |

0.9% |

1.3% |

1.4% |

||

Table A2

|

Ancillary calculations |

|||||

|

Rand billion |

|||||

|

Social grants |

2019/20 |

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

2022/23 |

Average annual increase |

|

CPI increase |

4.3% |

4.9% |

4.8% |

4.8% |

|

|

Increase in demand |

1.7% |

1.7% |

1.7% |

1.7% |

|

|

Social grants |

175.3 |

185.9 |

198.4 |

211.4 |

|

|

Health budget |

|||||

|

Baseline expenditure |

222.7 |

238.5 |

257.2 |

272.9 |

7.0% |

|

Input reduction |

1.3% |

1.8% |

2.0% |

||

|

Revised |

222.7 |

235.5 |

252.5 |

267.5 |

6.3% |

|

Population (thousands) |

58558 |

59309 |

60042 |

60756 |

|

|

Real per capita |

100.0 |

100.1 |

101.1 |

101.0 |

|

|

Public debt |

|||||

|

Debt to GDP ratio (per cent) |

|||||

|

2019 Budget |

56.2 |

57.8 |

58.9 |

59.7 |

|

|

MTBPS without Eskom |

59.8 |

62.8 |

65.7 |

68.0 |

|

|

MTBPS with Eskom |

60.8 |

64.9 |

68.5 |

71.3 |

|

|

MTBPS with Eskom and adjustment |

60.8 |

64.2 |

66.8 |

68.6 |

|

|

Debt (Rand billion) |

|||||

|

MTBPS with Eskom |

3120.1 |

3536.3 |

3976.0 |

4411.6 |

|

|

MTBPS with Eskom and adjustment |

3120.1 |

3496.5 |

3876.4 |

4244.3 |

|

[1]See, for instance, Neil Coleman, If SA wants to emulate the Portuguese success and avoid the Greek disaster, we must stop full-blown austerity, Daily Maverick, 30 October 2019