Introduction

The government’s economic policy cards are on the table. They have been put there by the Presidential address to Parliament on 15 October[1] and the Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (“MTBPS”) delivered by the Minister of Finance on 28 October. The policy attempts to achieve two goals simultaneously: to ward off an impending fiscal crisis and to improve investment to the point where it can underpin a respectable rate of economic growth. Both need urgent attention. The political economy question is this: can a coalition of interests be maintained to sustain the policy for several years?

The economic context

The economic fundamentals can be summarized in three graphs.

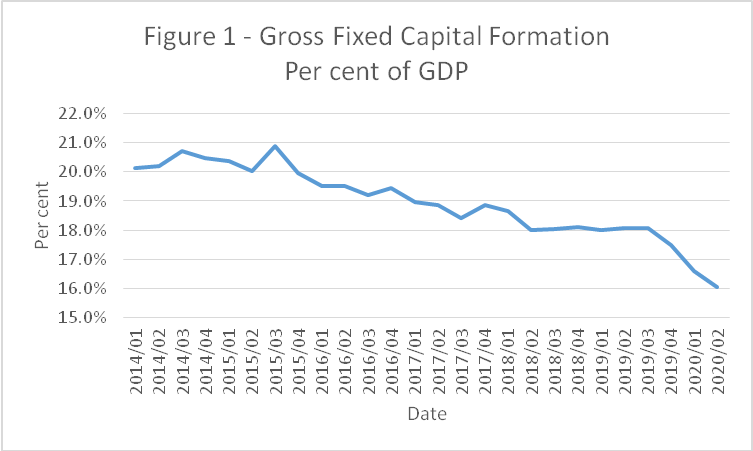

Figure 1 shows gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP from the first quarter of 2014 to the second quarter of 2020.

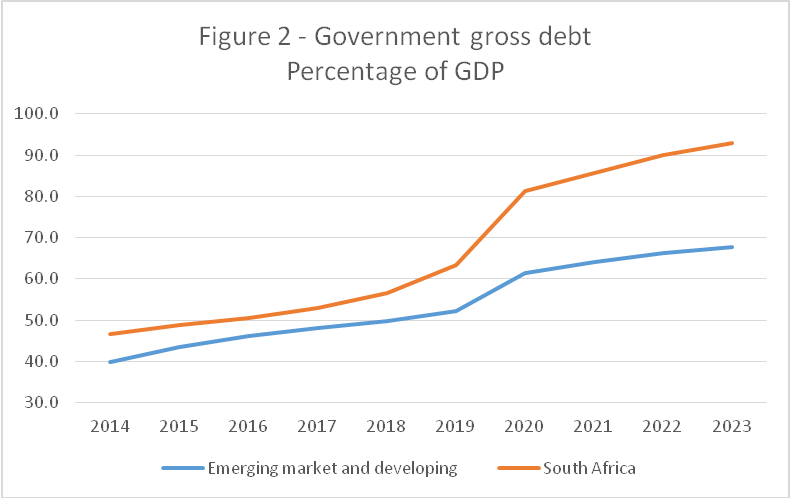

Figure 2 compares government gross debt as a percentage of GDP between South Africa and emerging market and developing economies as a whole from 2014, and projected to 2023. The MTBPS projection for South Africa and the International Monetary Fund projection for emerging market and developing economies are used.

Source: SA Reserve Bank online statistics

Sources: MTBPS and IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020

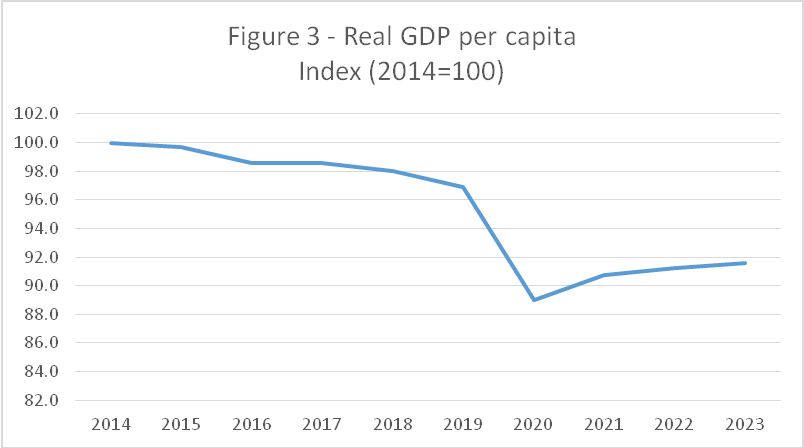

Figure 3 graphs the real GDP per capita from 2014 to 2023, using the MTBPS projection.

And here’s the crux: government policy is aiming to shift resources from consumption to investment at a time when real GDP per capita is well below the level achieved in 2014. This strategy has substantial risks.

Sources: See Annexure

Economic risks

The fiscal risks have been outlined in a previous brief[2]. They are to the downside and, if realized, would lead to an upward movement in the government bond yield curve and increased inflation, putting downward pressure on investment.

There are further risks. It is intended that public sector infrastructural investment will crowd in much more private investment. The risk is that the crowding in effect will be smaller than anticipated. There are three things which can be done to reduce the risk:

- Confine infrastructural investment by type and location to where private sector economic development can be expected and there are good prospects for payment for the services rendered by public sector investment.

- Keep procurement costs to a minimum. At present, there is movement in the wrong direction. The Minister of Finance published a draft Public Procurement Bill earlier this year which would extend preferential procurement in a number of directions. Every set aside and every increase in weight of considerations other than price and quality in the awarding of contracts increases costs and reduces what is delivered for a given allocation of financial resources. These measures create room for a particular type of fronting, whereby a preferred provider obtains a contract at elevated prices and immediately subcontracts the work at market prices, pocketing a pure rent which develops no new capacity.

- Ensure strict compliance with the Public Finance Management Act in all aspects of contracts, prohibit extension of existing contracts and carry out thorough checks on tendering enterprises to make sure that no public office bearer has an interest in them. Two Daily Maverick articles illustrate the problem: civil servants found to be doing business unlawfully with the state rose by almost 50% between February 2019 and April 2020[3], and less than 10% of the total amount of R230-million paid to the main contractor for the Free State asbestos audit ended up being utilized for the specified work[4].

Political risks

Start with a comment from Carol Paton in Business Day on 29 October:

Finance minister Tito Mboweni has done the right thing for the country in cutting spending to ultimately reduce debt, but in doing so he has set the stage for social conflict.

But this cannot be read to imply that the Minister might have set out an alternative path which would avoid social conflict. No such path is available. Realization of downside risks to the MTBPS public finance projections or poor leverage and value for money from public investment will result in a worse GDP outcome. Social conflict, arising from disappointed expectations, is baked in during the medium term.

Every fiscal crisis is a political crisis. The ANC government’s crisis is that it cannot continue to deliver to all its constituencies - black business, both legitimate and corrupt, the unions, the urban and rural poor, university students, emergent farmers, employees of the state, state-owned enterprises – at the rate to which they are accustomed to expect. The account is overdrawn and retrenchment is inevitable. The only question is: will retrenchment be orderly or disorderly?

The risks of disorderly retrenchment are:

- Disaffection among Cabinet members as the implications of the economic strategy become more apparent. No member of the Cabinet can foresee exactly how things will turn out, but some members will understand the implications of the strategy more than others. Economic expertise is not distributed uniformly throughout the Cabinet. Some members may come to find the costs of the strategy more than they bargained for.

- Factional intrigue within the ANC National Executive Committee. It is hard to imagine that the economic strategy will not become a major issue in the struggle between factions. Horse trading could easily lead to weakening of the strategy, particularly if its political cost becomes manifest.

- State owned enterprises. For a long time now, state owned enterprises have been playing a game of chicken with the government over bailouts, knowing that, to date, the government has always blinked first. One reason for this is the failure of board members to act in the interests of government as shareholder. Negligence, incompetence and corruption have all played a part in allowing this to happen. Principal-agent alignment needs much tightening up. Another way of mitigating risk is the attachment of strict conditions to financial support, increasing the pressure on management to adapt to circumstances by their own efforts.

- Public sector employees and COSATU. Here a showdown is inevitable. To mitigate risk, government needs to start preparing for it now.

- Service delivery protests. Service delivery cuts are coming, and with them service delivery protests. The impact of these protests will vary by geographic location. Those closest to the heart of the economy will have the greatest impact.

The interests of two further actors

Strategic decisions made by two further actors will affect the risk in the government’s economic strategy.

Business stands to gain by the development of new investment opportunities. Its gains will depend on complementary public sector investment and business pressure should be focused on having its particular needs met. This pressure should have the effect of increasing the leverage of public sector investment, contributing to the success of the government’s strategy.

The government can expect no help from the left, populist or otherwise. On the other hand, parties to the right of the government have some strategic thinking to do. Expansion of the private sector is in their interest, as well as retrenchment of a patronage network to which they have no access. It is impossible, and in any event undesirable, to expect competition between them and the government to disappear. But it is possible for these parties to work out a strategy of supporting the government when it is moving in the right direction from their point of view, while opposing it if it moves in the wrong direction. Intelligently applied, this strategy should have a constructive outcome.

Conclusion

We are at the beginning of a long and complex game, with the possibility of both straightforward and subtle moves, and luck playing an important role. At stake is whether the country starts to move forward again, or whether it stagnates or –more likely - continues to regress.

Charles Simkins

Head of Research

charles@hsf.org.za

Annexure

|

Real GDP per capita in 2023 |

||||||

|

Year |

GDP |

Population |

GDP per capita |

GDP |

GDP per capita |

Index |

|

R billion |

thousands |

current prices |

deflator |

2020 prices |

2014=100 |

|

|

(2020=100) |

||||||

|

2014 |

3805 |

54 544 |

69760 |

75.3 |

92582 |

100.0 |

|

2015 |

4050 |

55 386 |

73123 |

79.2 |

92273 |

99.7 |

|

2016 |

4359 |

56 208 |

77552 |

85.0 |

91284 |

98.6 |

|

2017 |

4654 |

57 010 |

81635 |

89.4 |

91282 |

98.6 |

|

2018 |

4874 |

57 793 |

84336 |

92.9 |

90748 |

98.0 |

|

2019 |

5078 |

58 558 |

86717 |

96.7 |

89703 |

96.9 |

|

2020 |

4885 |

59 309 |

82366 |

100.0 |

82366 |

89.0 |

|

2021 |

5240 |

60 042 |

87272 |

103.8 |

84045 |

90.8 |

|

2022 |

5553 |

60 756 |

91398 |

108.2 |

84469 |

91.2 |

|

2023 |

5877 |

61 453 |

95635 |

112.8 |

84764 |

91.6 |

Sources:

GDP – SA Reserve Bank and MTBPS

Population – United Nations, World Populations Prospects, 2019

GDP deflator – IMF World Economic Outlook and MTBPS

[1] Important ancillary documents include: Building a new economy: Highlights of the Reconstruction and Recovery Plan (https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202010/building-new-economy-highlights-reconstruction-and-recovery-plan.pdf), Building a society that works: Public investment in a mass employment strategy to build a new economy (https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202010/presidential-employment-stimulus.pdf) , Sustainable Infrastructure Development Symposium South Africa booklet (https://sidssa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SIDSS-Editorial-V10.pdf), and South African Presidential Economic Advisory Council, Briefing notes on key policy questions for SA’s economic recovery, October 2020 (https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-10-13-ramaphosa-secures-crucial-backing-for-a-thumping-cut-in-public-sector-wage-bill/)

[2] Charles Simkins, Financing government debt, HSF Brief,

[3] Marianne Merten, Words are not enough: fighting corruption requires action, time frames and political will, Daily Maverick, 11 September 2020

[4] Peter-Louis Myburgh, Public Protector confirms more than R 200 million squandered in Free State asbestos audit, Daily Maverick, 16 May 2020