Introduction

During the recent collapse in global economic activity as a result of COVID-19, and along with it a crash in the stock-markets, many have hoped for a “V-shaped” recovery. This means that the quick fall in economic activity caused by lock-down measures would be followed by a quick recovery as lock-downs are eased and economies begin to open up again. The logic behind this is that the economic contraction caused by the lock-downs was self-imposed and the recovery therefore is also ours to control, at our terms and at our pace.

Looking at stock-markets alone, it would seem that this view might be right in the United States. Markets have rebounded signalling that “V-shaped” recovery is anticipated.

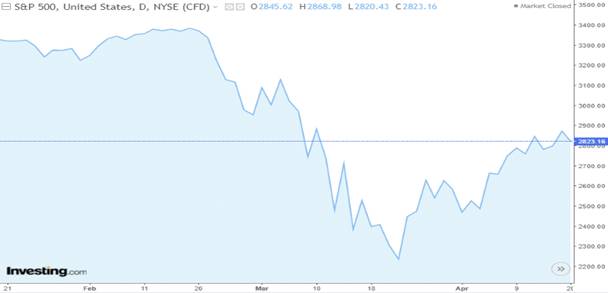

Below is a graph of the price movement of the S&P500 index[1] from late February, when it became clear that COVID-19 was to become a global issue, until the time of writing (21 April 2020):

During this period the S&P500 fell by over 33% and then rose by 25%, which means that the S&P500 experienced a market crash and followed up with a “bull” market in about two months. If the stock market price recovery continues at this pace it would buck the historical trend of market recoveries after a crash taking years as opposed to months.

However, the stock-market recovery is surprising as there is still significant uncertainty around the lasting impact on the economic impact of COVID-19, with only a very partial return to business activity to date and no vaccine or effective treatment of the virus.

The US economy and the Federal Reserve System

Spurring on the markets and those who believe in the “V-shaped” recovery are the recent actions by the US Federal Reserve System (Fed) to try and limit the damage caused by lock-downs. There is an adage which states “do not fight the Fed.” It means that if the Fed is taking measures to support the economy, ultimately it will succeed and the stock market prices will recover. This has been the case in the past.

The Fed’s recent actions are unprecedented. It has moved faster than in the wake of past market crashes, has already provided more than double the support than after of the 2008 financial crisis, and stated that it will do “whatever it takes” to help the US economy. Not only is it buying government debt but also bonds issued by private companies too, including those rated below investment grade or “junk.”

Looking at the effect of the downturn on the real economy, over 22 million Americans have lost their jobs since shutdowns began, obliterating all previous records. A decade of US employment growth has been reversed in a single month.[2]In the graph below, this is shown by the straight blue line on the far-right which reaches towards 7 million:

Internationally, the International Monetary Fund's global economic predictions are the worst since the Great Depression.

Although the crisis has created winners, such as Amazon whose shares have hit new highs, most companies are badly affected. More than half of US workers are employed by small and medium-sized enterprises, which are struggling to get all the financial assistance on offer.[3] Though new programs are in the pipeline, in mid-April the Small Business Administration, tasked with managing a US$349 billion fiscal program to help support such businesses, said it was unable to accept new applications as it was already oversubscribed.

There are going to be many bankruptcies, with the average bankruptcy taking 260 days to work out. Some companies will recover with bankruptcy protection, but management will be distracted and employees will be searching for more secure employment. Even companies that don’t need bankruptcy protection will need time to rebuild credit facilities, rehire personnel and re-establish customer relationships.

Consider too the complexity of the global supply chain. More than 90% of Fortune 1,000 companies[4] have at least one tier-2 (secondary) supplier[5] in Hubei, the Chinese province around Wuhan, the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Fewer than one in five of these companies have a tier-1 supplier in the region, but one failed link can disrupt the whole chain. The link can be replaced, but it takes time.

Businesses will take longer to recover than those holding onto the “V-shaped” recovery narrative think. Consumers will only return to familiar spending habits if they have regular income and the government does not raise taxes to pay for the current spending. At best, corporate earnings will only be partially recoverable as large item purchases by consumers, such as cars and electrical goods, can be put off for years. Dividend declarations by listed companies will also be cut or cancelled.[6]

US corporate debt and the Federal Reserve System

Around 40% of all US corporate debt was rated just above junk going into the crisis. Meaning it is considered high-risk and will need to pay higher borrowing rates, and with further downgrades from credit ratings agencies all but guaranteed, some companies will lose access to credit altogether. Moody’s Ratings Agency estimates that the default rate for junk-rated companies could reach 10%, compared to a historical average of 4%. And there is no guarantee that the unprecedented buying of corporate bonds by the Fed will avoid this outcome.

The Fed becoming the buyer and lender of last resort, alleviating the pain and taking the place of the markets by buying even junk rated corporate bonds, raises the risk of moral hazard. The hazard lies in creating the expectation that government will in future protect businesses from unpleasant financial consequences of their actions. Such a mind-set may see companies purchasing their own shares, taking on more debt or leveraging acquisitions to a greater extent. If plans go well, profits will increase. If they do not losses will be increased, reducing the possibility of survival during difficult times. Moral hazard encourages risky behaviour.

One also has to wonder, how will the Fed will avoid acquisition of corporate bonds from over-leveraged firms, how will a fair price for the bonds be established, and how will companies being able to borrow no matter their underlying fundamentals help the economy?[7]

Conclusion

A wave of defaults, credit downgrades to junk, bankruptcies and price drops in real assets would change the positive stock market narrative quickly, as would a second wave of the virus. Growth in anticipated corporate earning is what drives stock-market valuations, and no one can guarantee that this will emerge any time soon. The US’s monetary and fiscal response to the crisis has been spectacular, but can it prevent a permanent loss of growth if people’s consumption, travel and working practices have been altered fundamentally?

A “wheelbarrow shaped” recovery – a long, drawn-out bottom and a slow, upward recovery –is a more likely scenario. Investors, businesses, governments and individuals should prepare for it. But even this, according to the World Economic Forum, assumes that the lock-down restrictions are fully lifted in the next few months.[8]

The world’s most famous investor and bargain hunter, Warren Buffet, is not buying into a “V-shaped” recovery scenario. His lack of participation in the recent COVID-19 induced market crash is in stark contrast to the 2008 financial crisis, which saw his investment company, Berkshire Hathaway, spend tens of billions on new investments. The company’s vice chairman, Charlie Munger, told the Wall Street Journal in recently that “[w]e just want to get through the typhoon, and we’d rather come out of it with a whole lot of liquidity. Nobody in America’s ever seen anything else like this, this thing is different. Everybody talks as if they know what’s going to happen, and nobody knows what’s going to happen.”[9]

Charles Collocott

Policy Researcher

charles.c@hsf.org.za

[1] The S&P 500 index represents the 500 largest companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange,

[2] Individuals applying for government benefits due to losing their jobs.

[4] Largest 1,000 US based companies.

[5]Tier 1 and Tier 2 refer to the manufacturing industry, where Tier 2 companies supply Tier 1 companies with the products needed.

[7] Howard Marks, Knowledge of the Future, 2020.