Lindela – a name evoking twenty-two years of abuse and infamy. The red brick fortification looms just west of Johannesburg on the outskirts of Krugersdorp. In 1996, it was converted from a miners’ hostel compound – a type of housing notorious for the abuse suffered within it – to South Africa’s single specialised holding facility for irregular immigrants awaiting deportation.

This brief is a story of two government departments – the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) – and the latter’s ill-fated alliance with Bosasa. These three entities have woven together South Africa’s deportation regime, in all its corruption and mismanagement.[1]

The deportation regime and oversight

SAPS arrests suspected irregular immigrants and detains them at a police station until their immigration status is determined. Detention must occur at one of the 445 police stations nationwide, declared as adequate places of detention for irregular foreigners pending deportation or transfer to Lindela.

The DHA determines the status of immigrants in SAPS custody. If found to be illegal, the DHA charges the individual, who must appear before court within 48 hours of arrest. There, a notice of deportation is served, triggering the detention period. The DHA determines the facility (a designated police station or Lindela) at which the individual will be detained awaiting deportation. The DHA is legally and administratively responsible for the transport, holding, processing, and repatriation of an irregular foreigner.

Bosasa, now called African Global Operations (AGO), runs Lindela on the DHA’s behalf. It is responsible for catering, health, safety, accommodation and services at the facility.

The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) monitors Lindela through inspections of the facility and reporting by the DHA. As required by a 2014 High Court judgement[2], the DHA must allow the SAHRC regular access to Lindela and provide it with weekly detainee lists, so that the SAHRC can monitor the length of the period over which each detainee is held awaiting deportation.

Other humanitarian groups, including Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and People against Suffering Oppression and Poverty (PASSOP), monitor Lindela in partnership with the SAHRC. Their access is granted and inspections conducted alongside those of the SAHRC. LHR conducts individual case consultations with detainees approximately every two weeks.

Lindela’s troubled tender history

Bosasa has never lost the tender for Lindela. Even in 2005, after 21 deaths were reported at the facility in the space of eight months, Bosasa’s contract was renewed. In 2015 it was renewed again to 2020. Thus Bosasa runs Lindela to this day.

The story began in 1996, when Dyambu Operations won the tender to run Lindela just twelve days after it was requested. Dyambu, which would be renamed “Bosasa” four years later, was owned by the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL) leaders, who brought on Gavin Watson as CEO.

The League sold its shares after the ANC decided that it would no longer hold direct interest in companies, and by 2004, the company’s shareholders were the Watson’s family trust (26%); Bosasa Directors Carol Mkele and Joe Gumede (51.8%) and the Bosasa Employees’ Trust (22.2%).[3]

The DHA pays Bosasa R9.5 million per month to run Lindela. The contract is not publicly available, so it is not clear what this money goes towards. Both entities have resisted access to information applications for the contract, and Bosasa is precluded from commenting publicly on allegations, referring all queries concerning Lindela to the DHA.

In 2019 at the Zondo Commission, after the allegations of Bosasa’s systematic bribery of government officials for tenders, former Bosasa employee, Frans Vorster, revealed that Lindela funds have been syphoned annually into executives’ pockets over the festive season. Bosasa would allegedly buy 2000 extra mattresses for the facility nearing the end of the year and ensure that they were occupied, in order to cash in on the DHA’s pre-existing ‘per person per night’ fee.[4]

The history of criticism

Between 1997 and 2017, humanitarian groups[5] have produced a corpus of reports on the state of Lindela. Criticisms levelled at Bosasa have included:

- Inadequate medical care and oversight, with high death rates amongst the detainee population and the absence of entry screening for diseases.[6] In June 2018, MSF submitted an official complaint to the Office of Health Standards Compliance (Health Ombudsman). The complaint concerns low-quality healthcare; lack of oversight for the clinic; poor implementation of health standards; inadequate outbreak management; and lack of social and mental healthcare.

- Poor living conditions, including concerns of hygiene, overfilled cells, interrupted sleep and poor nutrition.

- Instances of abuse of detainees by guards.[7]

- Bosasa corruption, including allegations of misappropriation of Lindela funds and bribery for tenders.

Criticisms levelled directly at the DHA have included:

- The recurrent detention of minors, including four-year-old Sinoxolo Hlabanzana who died at Lindela.[8]

- Neglect of the procedural rights of detainees, such as the absence of legal representation and translators.[9]

- Detention for periods beyond those prescribed by law – 30 days, or 120 days with a court extension.[10]

- Withholding or restricting access to Lindela for monitoring purposes, particularly from human rights groups.[11]

Current Issues

1. Lack of investigation and information

Some of the issues mentioned above have not been reported on in the last two years.

In 2014, the SAHRC demanded that the DHA furnish detainee lists to the SAHRC, so that the latter could track the detention periods of immigrants. The DHA was ordered by the High Court to report annually to the SAHRC, with quarterly reports listing every individual who is approaching being held for an unreasonable or illegal length of time at Lindela.

The SAHRC reported in 2017 that it had been able to fulfil its constitutional mandate of monitoring Lindela with unrestricted access and through reports regularly submitted by the DHA, containing lists of detainees.[12] In its 2017 Annual Report, a section was dedicated to Lindela which included observations and key recommendations.[13]

No report on Lindela has been published by the SAHRC since, and the SAHRC did not respond to our enquiry on this and other matters.[14] Moreover, neither MSF nor LHR have inspected the facility for over a year – inspections that must take place in partnership with the SAHRC, which has not answered our request for the date of its last inspection.

This ostensible decline in inspections and public information are a cause for concern. We hope that the SAHRC’s silence does not reflect apathy or a private motive.

2. Bosasa benefits from an under-occupied Lindela

The DA was granted access to Lindela in February 2019. Their purpose was to inspect and highlight conditions ‘in light of the massive amount of government funds that have been pocketed by Bosasa and the alleged human rights violations’.[15]

MP Jaques Julius reported that ‘there were notable improvements at Lindela, particularly in the medical facility since our last oversight visit’. ‘We did however find that the facility is underutilised as only 800 irregular immigrants are currently being detained at the facility which has the capacity of accommodating 5000 people’.[16]

We contacted Mr Modiri Matthews – the Chief Director of the Inspectorate at the DHA – to confirm these figures. He stated that there are, on average, between 1500 and 2000 deportees processed at Lindela per month. In response to the DA’s report of 800 people at a given time, he said that if a large number of deportees are cleared in a particular week, the occupancy level can be low until another group is admitted.

Even so, Lindela is operating at around 30% of its full capacity. What happens to the R9.5 million per month (R1.5 billion over the last 15 years) of tax payer money that is pocketed by Bosasa to run the facility? The DA and COPE have called for the contract to be cancelled and for funds to be returned – a demand that may be realised through the impending liquidation of Bosasa.

3. While Lindela is empty, police cells are full

Another glaring question is why, given the emphasis placed on undocumented immigration to South Africa, is Lindela 30% full?

While Lindela runs under capacity – a cash cow for a disgraced Bosasa – it emerged in Parliament in February 2019 that SAPS is burdened by having to detain and accommodate arrested immigrants in jails.[17]

SAPS stated its case as follows: The requirements for holding facilities for irregular immigrants must adhere to human rights standards that exceed those of common criminals. SAPS having to fund these services presents a ‘critical challenge’. SAPS spent, on average, R1.7 million per month in 2018 providing meals to these detainees, and believes that it is entitled to have that money reimbursed by the DHA.[18]

Using these meal costs, SAPS concluded that around 9100 immigrants are moving through SAPS cells per month (confirmed for the month of July 2018), while Lindela processes between 1500 and 2000 – a state of affairs from which Bosasa and the DHA win and SAPS loses.

SAPS suggested that if an extension is added to a detainee’s initial 48-hour status-determination period, the individual should become the responsibility of the DHA and be moved to Lindela within 7 days.[19] Clearly, SAPS and the DHA should begin communicating over this issue.

4. Arbitrary arrests and detention

The DHA reported only 15 033 deportations in the 2017/18 financial year. That is an average of 1 253 deportations per month – far short of the 9100 people processed by South African prisons and the 1 500 to 2 000 per month processed by Lindela. These statistics suggest that only 14% of suspected irregular immigrants arrested in South Africa in 2018 ended up being deported.

Like citizens, foreign nationals have the right not to be arrested or detained arbitrarily.

SAPS can arrest an individual as an irregular foreigner in terms of the Immigration Act, on ‘reasonable grounds’ at the officer’s discretion. The scope of discretion was clarified in Udle v Minister of Home Affairs and Another, where the Court confirmed that an officer must exercise discretion in favorem libertatis (in favour of freedom).[20]

Despite the SAHRC’s 1999 recommendations, spot checks and sweeps are included as a modus operandi for the apprehension of suspected foreign nationals, although they fail to satisfy the criteria of ‘reasonable grounds’ and contribute to a high rate of unfounded arrests.[21] SAPS’ mass arrests of foreign shop owners in August 2019 (a factor contributing to xenophobic resurgence) and foreign church-goers in October 2019 are recent examples. After the raid at the Full Gospel Church in Mthatha, all of those arrested (Congolese refugees including the Pastor) were found to be legal and released.[22]

LHR, in their 2018 letter to Cyril Ramaphosa, wrote that ‘people are wrongfully and unlawfully detained under the current immigration legislation, that the process of arrest and detention of would-be immigrants is arbitrary and, therefore violates the rights of citizens and other residents’. They argued that there is strong evidence to suggest that black and darker-skinned individuals are more vulnerable to arbitrary arrest.[23]

The unscrupulous arrest and detention of immigrants appears an inefficient and costly preoccupation. SAPS resources could better be channelled into addressing rising crime levels, and the DHA’s migration budget could be better applied to address border control, corruption and mismanagement in the migration regime.

5. Procedural flaws in arrests and detention

The African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF), in a 2017 report, found ‘non-compliance with respect to procedures for arrest of foreigners and procedural rights, including sentencing procedures, the issuance of deportation orders, extension of detention orders and the provision of interpreters’[24].

Despite SAHRC recommendations, immigration officers do not appear to be keeping proper records of arrest, including the date and place of arrest; the reason for arrest, or any explanation advanced by the suspect, including documents produced.

Arresting and immigration officers are not exercising sufficient caution when arresting and detaining individuals who may be minors. This is confirmed by the SAHRC’s 2017 report of the frequent occurrence of arrest and detention of unaccompanied minors at police stations and Lindela.

LHR reported a ‘denial of constitutional and civil rights’ at police stations, citing routine cases of the incarceration of people for periods ranging from weeks to months, without the extension of detention as per the Immigration Act.[25]

Finally, while laws and guidelines exist, there is no self-reporting or independent monitoring system of SAPS detention facilities. Until the court order establishing the SAHRC oversight of Lindela, the same was true for that facility.[26]

The future of deportation

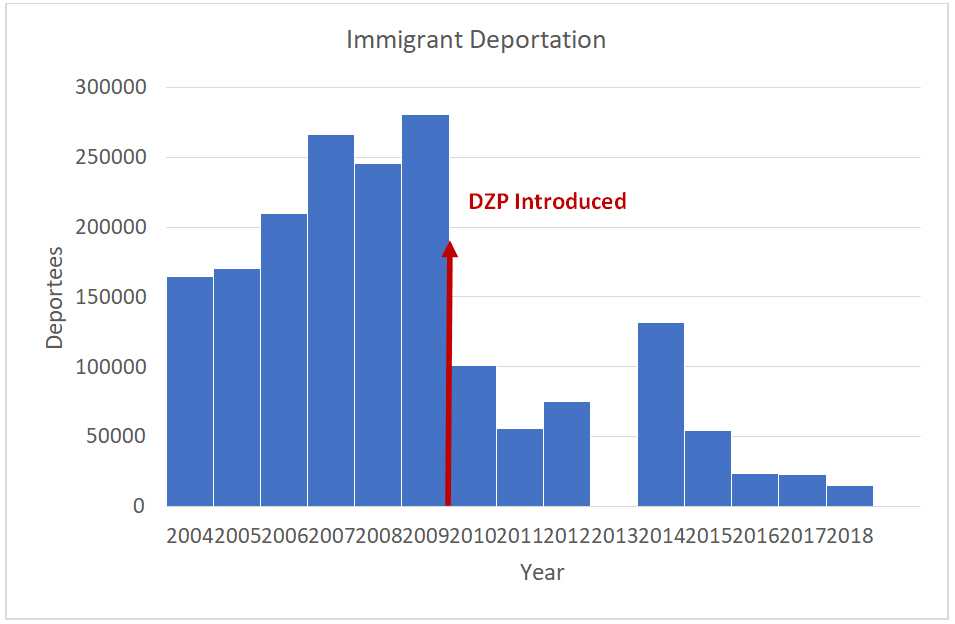

Since the introduction of the Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project in 2010, used to regularise undocumented Zimbabwean immigrants until conditions in their home country improve, deportations have plummeted. In the context of the government’s sustained emphasis on deportation, this suggests that there are far fewer irregular immigrants in South Africa.

Source: DHA Annual Reports 2003 – 2018

In the face of these statistics, government is yet to revise its preoccupation with illegal immigration and deportation – a costly and inefficient fixation that criminalises immigrants and fuels xenophobia. Of course, the entity that has stood to benefit most from the status quo is Bosasa, and all those officials that solicit bribes from undocumented immigrants, or share in Bosasa’s loot.

Mr Modiri Matthews of the DHA commented that the Bosasa contract to run Lindela will expire in November 2020 and that a new tender process is to commence shortly. This process may be hastened by the liquidation of Bosasa.

As a new chapter approaches for South Africa’s deportation system, the DHA should focus on its tender selection, resource allocation, transparency and reporting to the SAHRC. The SAHRC should focus on its monitoring responsibilities and its mandate to communicate, educate and protect. SAPS should rethink its motives for and procedures of arrest, so that detention can be used as a last resort.

Tove van Lennep

Researcher

tove@hsf.org.za

[1] The deportation system includes inputs/ assistance from the Department of Justice and the Department of Health

[2]South African Human Rights Commission and Others v Minister of Home Affairs: Naledi Pandor and Others [2014] ZAGPJHC 198

[3] Ibid.

[4] Mail & Guardian: Bhekisisa, 6 February 2019. This is how SA toddler died at the #Bosasa-run Lindela

[5] Among others, the SAHRC; LHR; PASSOP; MSF; Judges Edwin Cameron and Dikgang Moseneke of the Constitutional Court etc.

[6] The death of 21 people at Lindela within 8 months (2005); lack of medical care and oversight (2012); lack of HIV and TB testing and no provision of condoms (2014); lack of entry screening for diseases (2017).

[7] Detainees involved in a hunger strike claim to have been attacked by guards with rubber bullets and batons (2014). Detainees are beaten by guards with pipes and fired on at close range with rubber bullets – an account disputed by the DHA but confirmed by MSF medical examinations (2017).

[8] Four-year-old boy, Sinoxolo Hlabanzana, dies of a fever at Lindela as a result of inadequate medical facilities (2004); A report by MSF details the illegal detention of dozens of minors over the years (2016).

[9] No provision of an independent complaints mechanism for inmates to report abuse (2017); the disregard of detainees’ rights or failure to notify detainees of their rights by Lindela officials (2017).

[10] The SAHRC reports that 52 people have been detained at Lindela for more than 120 days in 2014, and 4 for more than 300 days (2014). A court order specifies that irregular immigrants may be held for 30 days as efforts are made to deport them, or for another 90 days if a court issues a warrant (2014)[10]. The SAHRC reports continued detention of undocumented immigrants for periods beyond those prescribed by the law (2017).

[11] Following years of restrictiveness, a group of civil society actors have demanded access to Lindela for the SAHRC, enforced by the 2014 High Court order. LHR reports on limited access to the detention centre, and each visit requires 48 hours’ notice (2017)[11]. The SAHRC reports that it enjoys unrestricted access to Lindela (2017), while other human rights groups in partnership with the SAHRC report restricted access (2014 – 2019).

[12] SAHRC, 2017. Annual Report

[13] SAHRC, 2017. Annual Report: pp 29-33

[14] We first contacted the SAHRC on 15 October 2019 by email. After 7 days, we sent a follow up email, which was responded to on 23 October. We were referred to the Research Advisor to SAHRC Commissioner Nissen. He referred us to the Research Advisor of Commissioner Makwetla who was on leave until 29 October. She has not yet responded to our email. In the meantime, one of the initial respondents re-referred us to the Advisor of Commissioner Nissen. We emailed him on 30 October and he replied shortly afterwards, agreeing to answer our questions “in due course”. After no response by 4 November, we attempted to get hold of the Advisor both through the SAHRC office line and on his direct line. We left messages on both occasions and have not yet received a response.

[15] DA: Jacques Julius, 27 February 2019. #Bosasagate: Lindela underutilised while SAPS spend millions to detain irregular immigrants

[16] Ibid.

[17] PMG, 26 February 2019. Immigration Amendment Bill: Police Minister & Home Affairs Deputy Minister input; Home Affairs office accommodation: Minister of Public Works input

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20]Ulde v Minister of Home Affairs and Another (320/08) [2009] ZASCA 34

[21] APCOF, 2017. “Migration and Detention in South Africa” in Policy Paper No. 18.

[22] Maverick Citizen, 28 October 2019. Anger and fear as Home Affairs officials raid Mthatha churches

[23] Lawyers for Human Rights, 20 June 2018. Open letter to President Ramaphosa on World Refugee Day

[24] APCOF, 2017. “Migration and Detention in South Africa” in Policy Paper No. 18.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.